This is the third in a series of articles focused on classic elements of change management content, updated and augmented with my own perspectives and experience. In the first post, Strategic Risk Factors, I have provided some of the history behind this series. The series is primarily written for change management practitioners, but I hope it will also be useful for others who are interested in making organizational changes more successful.

Today’s Focus: Commitment

Commitment is one of the most important outcomes we seek in organizational change. It reflects the degree to which people have incorporated new mindsets and behaviors into their way of working. It is the bridge between the new processes, models, and approaches we put in place and the achievement of the business outcomes we are pursuing. In this post I want to share with you a model of commitment, and provide some commentary on how it might be most useful to today’s leaders and practitioners.

Here is the model as I learned it nearly thirty years ago. I’ve seen various versions of it since then, but here is the “classic” I am most familiar with. This material is adapted from and used with permission of Conner Partners.

*****************************************************

Building Commitment to Organizational Change: Classic Model

Defining Commitment

People display commitment when they:

- Invest resources such as time, energy, and money to ensure the desired outcome

- Pursue a goal consistently over time, even when under stress

- Reject ideas or action plans that promise short-term benefits but are inconsistent with the overall strategy for ultimate goal achievement

- Stand fast in the face of adversity, remaining determined and focused in the quest for the desired goal

- Apply creativity, ingenuity, and resourcefulness to resolving problems or issues that would otherwise block the achievement of the goal

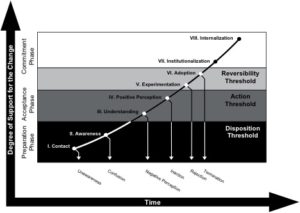

Given this, it is easy to see why commitment is so important to the success of organizational change. It is the cement that provides the critical bond between people and the change process. Yet most people involved in organizational change know very little about what commitment is, what it requires, how it is built, and how it can be lost. This graphic of the Stages of Change Commitment provides a model of how commitment can be built and sustained.

The model is shown as a graph. The vertical axis represents the degree of support for the new mindsets and behaviors, and the horizontal axis reflects the passage of time. The model consists of three developmental phases—Preparation, Acceptance, and Commitment—and the stages unique to each phase. Each stage represents a juncture critical to the development of commitment to change. A positive perception of change may stall (depicted by downward arrows) or increase (represented by an advance to the next stage). In addition, as people learn more about the change and what it will require, they may return to earlier stages in the process. The successful transition through a particular stage serves as the basis for experiencing the next stage.

The section below describes each of the phases and stages in this model. The subsequent section outlines approaches to helping people move through the sequence.

The Phases and Stages of Commitment

Preparation Phase

The Preparation Phase forms the foundation for later development of either support of or resistance to the change. There are two stages in the Preparation Phase: Contact and Awareness.

Stage I: Contact

Stage I is the first encounter individuals have with the fact that a change that may require them to shift their thinking and/or behavior is taking place in the organization. Commitment to an organizational change begins when employees—the sponsors, agents, and targets—pass through the Contact Stage. For example, if an organization decides to alter its marketing strategy, each role must come into contact with the change. The CEO, who will need to sponsor the change, may have this initial exposure to the prospect of change when reading a weak financial statement. The marketing director, who will likely be an agent for the change, may first hear of it through a senior staff person who has discussed the problem with the CEO. Members of the sales force, who will be targets of the change, may have their first exposure to it when a new sales approach is presented by the marketing director at a staff meeting.

Methods for delivering the first contact message can vary. There is a wide range of options including memos, staff meetings, personal contact, and other mechanisms. Regardless of the method, this first stage in the commitment process is intended to result in awareness that a change has taken place or may occur in the future. Contact efforts, though, do not always produce awareness. Sponsors and change agents are often frustrated when, after many meetings and memos about an initiative, some targets either are not prepared for the change or react with total surprise when it begins to affect them. The commitment model, which separates contact efforts from actual awareness of change, highlights the danger in assuming that contact and awareness are synonymous.

Outcomes for the Contact Stage are either:

- Awareness—which advances the preparation process, or

- Unawareness—in which no preparation for commitment will occur.

Stage II: Awareness of Change

In Stage II, employees know that a change is being considered or implemented. Awareness is established successfully when individuals realize that modifications affecting the organization’s operations (and potentially affecting them) have occurred or are possible. This requires that initial communications about the change reach the desired audiences and get the message across clearly.

This awareness, however, does not mean that employees have a complete understanding of how the change will affect them. They may not have an accurate picture of the scope, nature, depth, implications, or even the basic intent of the change. A sponsor, for instance, may be clear that he or she must lead people through a shift in marketing strategy but not understand what this will call for. An agent may recognize that he or she is being asked to apply a new methodology for executing the initiative, but not have a clear picture of the personal implications. And targets may perceive that a change is coming without knowing the specific ways they will need to alter their mindset and behavior. Before targets can progress toward acceptance, awareness must be developed into a general understanding of the change’s implications.

Outcomes for the Awareness Stage are either:

- Understanding—which advances the process to the Acceptance Phase, or

- Confusion—which reduces or precludes preparation.

Acceptance Phase

The Acceptance Phase marks passage over the Disposition Threshold. This is an important milestone; people shift from seeing the change as something “out there” to seeing it as having personal relevance. This perspective enables them to make decisions about accepting or not accepting their part in the change.

People often engage in individual activities designed to move themselves across this threshold—to help themselves move from awareness to understanding. They ask questions, pose challenges, seek additional information, and make inferences in an effort to clarify their picture of the change. Sometimes leaders wrongly interpret this behavior as resistance to the change initiative. Although it is possible for people to use endless questions and challenges as part of their resistance strategy, true resistance to the specific change at hand (rather than to the notion of change in general) can be manifested only when people understand it well enough to be able to formulate an informed opinion.

There are two stages of the Acceptance Phase: Understand the Change and Positive Perception.

Stage III: Understand the Change

In Stage III, people show some degree of comprehension of the nature and intent of the change and what it may mean for them. As they learn more about the initiative and the role(s) they are likely to play, people begin to see how it will affect their work and how it will touch them personally. These insights enable them, for the first time, to judge the change.

Judging something as positive or negative is a universal, and relatively automatic, process. When humans encounter something new or unfamiliar, our immediate reaction is to label it as positive or negative. Although we can consciously revise these immediate judgments, it takes effort to do so.

Each person’s judgment is influenced by his or her own cognitive and emotional filter systems—the unique set of lenses that he or she uses to view the world. These filters are developed through previous experience; some predispositions to view new things as dangers or opportunities may even be genetically linked. As a result of these filters, people can vary widely in their reactions to a new initiative. The same change may be viewed positively by some and negatively by others.

In addition, change of any significance usually has multiple aspects to it, and may produce both positive and negative reactions at the same time. For example, a target may have a negative view of a new company policy regarding relocation every four years but sees positive benefit in the level of job security he or she would experience. People combine these positive and negative reactions to form an overall judgment of the change.

Because the full implications of a change are rarely completely clear to anyone at the beginning, it is rare for people to be able to reach a comprehensive understanding early in the process. People move forward based on the information that is currently available. As new data become available, people may reevaluate their judgment of the change and move to a lower level on the Commitment Curve.

Outcomes for the Understanding Stage are either:

- Positive perception—which represents a decision to support the change, or

- Negative perception—which represents a decision not to support the change.

Note that a positive perception does not necessarily mean that people like the change, but rather that they see it as the best available course of action.

Stage IV: Positive Perception

In Stage IV, people form intentions to support or oppose the change. This is not done in isolation—they typically weigh the costs and benefits of the change against the costs and benefits of other alternatives, including doing nothing. Ideally, the benefits of a change to an individual so clearly outweigh the benefits of any alternative course of action that it requires little thought to decide to move forward. However, this is not typically the case. In many organizational change situations, the benefits of moving forward are only marginally more positive than the benefits of the best alternative course of action. In some changes, the path forward has such significant costs associated with it that the individual reaches an overall positive perception only because all of the alternatives are worse.

For instance, a leader may face a decision to lay off a large number of people from the organization. He is likely to see this as a tremendously difficult and costly move. But if he perceives that the alternative is the sale of the organization to a competitor who would be even more ruthless in the downsizing efforts, he may ultimately reach a positive perception about moving forward.

Positive Perception is an important stage in the process of building commitment, but at this point the change is still theoretical. People must begin to try out the new way of operating—they must alter their mindset and behavior.

Outcomes of the Positive Perception Stage are either:

- Experimentation—An initial trial of the new way of thinking and behaving, or

- Inaction—Failure to make initial shifts in thoughts and behaviors.

Commitment Phase

The Commitment Phase marks passage over the Action Threshold. In this phase, the perceptions that have been created in the Acceptance Phase result in actual commitment—observable changes in individual mindsets and behavior. This is a critical step—there are many situations in which people will say that they view a change as positive, but, for a variety of reasons, will not actually take the first steps to shift their behavior. As an example, consider recycling: If asked, most people would probably agree that recycling is a good thing, and even articulate their willingness to recycle. However, when it comes to taking action, many people do not consistently display recycling-supportive mindsets and behaviors.

Some reasons that people who see a change as positive might not take action include 1) the lack of a setting in which they can try the new behavior; 2) absence of needed skills; or 3) insufficient time, energy, or adaptation capacity to engage in the new behavior.

There are four stages in the Commitment Phase: Experimentation, Adoption, Institutionalization, and Internalization.

Stage V: Experimentation

In Stage V, individuals take action to test a change. This is the first time people actually try out the change and acquire a sense of how it might affect their work routine. This stage is an important signpost that commitment is growing but greater support is possible.

The critical importance of this stage is that no matter how positively people view a change prior to engaging with it, their actual experience with it will reveal a number of small or large surprises. Some of these may be positive, but others may involve unanticipated problems that may have significant negative consequences. If problems become too costly, pessimism regarding the change project will increase and may reach the “checking-out” level. This occurs when early, uninformed optimism for a project transforms into informed pessimism, and the individual’s original positive judgment shifts to negative.

Because of the inevitability of surprises, some degree of pessimism is unavoidable during change. Nevertheless, the confidence of those involved in a change increases as a result of resolving such problems. An environment that encourages the open discussion of concerns tends to solve problems, promote ownership, and build commitment to action. As these problems are resolved, a more realistic level of conviction toward the change builds. This conviction advances commitment to the Adoption level.

Outcomes for the Experimentation Stage are either:

- Adoption—Individuals continue their exploration of the new mindsets and behaviors, or

- Rejection—Individuals cease their exploration of the new mindsets and behaviors.

Stage VI: Adoption

Stage IV, Adoption, is reached after individuals have successfully navigated the initial trial period. The dynamics here are similar to that of the Experimentation Stage. Both stages serve as tests in which the individual and the organization assess the cost and benefits of the change. Longer-term trials can reveal logistic, political, and economic problems with the new way of operating that can lead sponsors, agents, and/or targets to question the long-term viability of the new approach and potentially make a decision to terminate the change.

The differences between the Experimentation and Adoption stages are important, even though their dynamics are similar. Experimentation focuses on initial, entry problems, and adoption centers on in-depth, longer-term problems. The former is a preliminary test of the change. It tries to identify its initial human and technical impact. The latter tests the ongoing implications of the change. Experimentation asks, “Will this change work?” Adoption asks, “Does this change fit with who I am as a person/who we are as an organization?” The shift is from “Can we do it?” to “Do we want to continue it?”

Although the level of time and resources necessary to reach Adoption is great, a change project in this stage is still being evaluated and can be stopped. Following are some typical reasons change projects are terminated after extensive testing.

- Logistic, political, or economic problems have been identified that could be found only after a long test period.

- The need that sparked the initial commitment no longer exists.

- The overall strategic goals of the organization have shifted and no longer encompass the change outcomes.

- People in key sponsorship or agent positions leave the organization or are no longer as active in the project as they once were.

If the change is successful after this lengthy test period, it is in a position to become the standard new way of operating. Outcomes for the Adoption Stage are either:

- Institutionalization—the new way of operating is established as a standard, or

- Termination—the change is ended after an extensive trial.

Stage VII: Institutionalization

Stage VII reflects the point at which people no longer view the change as tentative. They consider it standard operating procedure. It is now the norm; not, as in the past, a deviation. As part of the institutionalization process, the organizational structure may be altered to accommodate new ways of operating, and rewards and punishments implemented to maintain new mindsets and behaviors. What was once a change requiring substantial sponsor legitimization has become part of the organizational routine that is monitored by managers.

The move from Adoption to Institutionalization is a significant one, and a double-edged sword. The threshold that is crossed here is that of “reversibility.” Once a change is institutionalized, it becomes the new status quo. Even if the original reasons for legitimizing the change become void or people no longer believe it is worth the price to continue it, organizational systems and inertia are capable of maintaining the new way of operating long after it has served its usefulness. Ending an institutionalized pattern that is ingrained into the fiber of an organization is extremely difficult.

This stage reflects the highest level of commitment that can be achieved by an organization—the level above it, internalization, can only be achieved by individuals who make a personal choice to go there. Although institutionalization is sometimes all that is required to achieve the organization’s goals, it has some potential problems. If a change has been institutionalized but not internalized, those affected may be motivated to adhere to new procedures primarily to comply with organizational directives. For example, some change projects become institutionalized when targets are given the option to comply or face severe consequences. Their compliance is achieved by using organizational rewards and punishments to motivate them to conform despite their own private beliefs about the change. If their perception of the change is generally negative, but they have chosen to go forward because the costs of not doing so are prohibitively high, they will likely mimic acceptable behavior. They learn to say and do the “right” things, but their actions will not reflect their true perspective. Because their mindset (beliefs and assumptions) does not align with their behavior, a great deal of managerial pressure will be required to ensure the ongoing presence of the desired behavior.

The success of change does not always depend on the target’s personal investment. Some projects require only that targets “do as they are told.” But as the pace and complexity of change escalates, producing more turbulence in the workplace, many organizations have modified their views about workers needing to understand or support organizational changes. Forcing change implementation often results in a halfhearted effort without a full return on investment. Institutionalized change, as powerful as it is, only delivers the target’s behavior, not his or her mind and heart.

Stage VIII: Internalization

Stage VIII represents the highest level of commitment an individual can demonstrate to an organizational change. It reflects an internal motivation in which individual beliefs and desires are aligned with those of the organization, and there is a high level of consistency between individual mindset and behavior. While an organization can legislate the institutionalization of a change, internalization requires the active cooperation of each individual. At this last stage, people “own” the change. They demonstrate a high level of personal responsibility for its success. They serve as advocates for the new way of operating, protect it from those who would undermine it, and expend energy to ensure its success. These actions are often well beyond what could be created by any organizational mandate.

One example that may illustrate the difference between institutionalization and internalization is the comparison between compliance with speed limits vs. adherence to seatbelt laws. For most people, speed limits are institutionalized. It is primarily the threat of receiving a ticket that prevents them from exceeding posted speed limits by more than a few miles per hour, especially in zones where the limit is clearly below the maximum safe speed. In contrast, most people have internalized the commitment to wear seatbelts. They buckle up, and encourage others in their vehicle to do so, because they feel safer that way and believe it is in their own best interest to engage in this behavior.

Enthusiasm, high-energy investment, and persistence characterize internalized commitment, and it tends to become infectious. Targets who have internalized a change cannot be distinguished from sponsors and advocates in their devotion to the task and their ability to engage others in the change effort.

The time needed to move through the Experimentation, Adoption, Institutionalization, and Internalization phases will vary according to the individual, the organization, and the nature of the change project; the lines can be relatively clear or somewhat blurry depending on the situation. If a change is mandated, it can become institutionalized very quickly (but, as mentioned earlier, at a high cost of monitoring compliance). In other cases, institutionalization unfolds more gradually—as employees gain experience with the new way of operating, find ways to refine and improve it, and adjust to its long-range impact and requirements, the change gradually becomes a natural part of the organization’s culture or expected pattern of behavior. Internalization can begin very early in a change if the new way of operating is strongly aligned with individual beliefs and assumptions; it can also emerge along the way as individuals begin to see the advantages of the new approach. In some cases, it can fail to surface at all.

Understanding the steps and sequence for building commitment is a powerful advantage in building momentum for major organizational change.

*****************************************************

Commitment: Linda’s Commentary

This model has remained with me for nearly 30 years. It’s got staying power, because it captures something essential about change—the recognition that it is a process, not an event; that individuals move through it at their own pace; and that intellectual commitment and emotional commitment can proceed at different speeds. I’ve used it in change initiatives, often printing the “commitment curve” graphic as a large wall chart to track the progress of different groups through the transition. This model is one of the original inputs to the ADKAR process—Awareness and Desire track directly to Awareness and Positive Perception, while Knowledge and Ability help people move into the early stages of Experimentation and Adoption, and Reinforcement is essential to create Institutionalization.

Some of the insights that I gained while learning and using this model are that people can be at different stages of the process for different aspects of a change, that questioning is sometimes interpreted as resistance when in fact it is just an attempt to seek clarity, and that if we as change agents don’t do our work effectively, people can be stuck in unnecessarily long periods of confusion. Another thing that has become clear to me is that while work on the early parts of the process can be driven by change agents, leadership and sponsorship becomes much more important in building the higher levels of commitment—using communications and consequences to ensure Institutionalization, and inspiring people to generate the deep personal buy-in needed for Internalization.

I’ve developed my own personal test for the level of commitment people have achieved—how hard will they work to overcome obstacles they encounter in moving toward the future state. When people are in the Experimentation phase, even a small setback will often be enough to generate frustration and resistance. When they are in the Adoption phase, they’ll work a little harder to solve the problems they encounter. In Institutionalization, they will typically engage in substantive efforts to figure out how to make things work, and in Internalization, they are proactively looking for ways to anticipate and overcome challenges so they can help others increase their level of engagement in what they see as a better way of operating. To illustrate, think about the recycling example offered earlier. Someone who is in Experimentation will typically recycle a can if there is a handy receptacle to put it in, but will just toss it in the trash otherwise. Someone in Adoption might ask if there is a recycling bin, or look around to see if they can find one, but use the trash if they can’t locate an appropriate place for recycling. In Institutionalization, a person might carry the can with them until they locate a recycling site, or bring it home to recycle. In Internalization, a person might look for ways to place recycling bins in convenient places to help others engage in the desired behaviors more easily.

There are two things that I view differently now than I did when I first encountered the model. One is that I have become much more aware of the differences between transitional and transformational change, and recognize more clearly that this model is oriented around transitional change, where there is a fairly clear “future state” that people are moving toward. Since many changes are indeed transitional, the model has a lot of application in day-to-day change management work. But when I think about how it applies to transformational change, where people are going on a journey together into an unclear future, co-creating a new reality, I get a little stuck. Perhaps people can commit at different levels to the process of transformation—to stepping into the unknown, trusting the process, relying on one another and on their leaders to let things unfold—rather than to any particular desired state. I can imagine some people experimenting with letting go of the familiar, and finding it difficult, while others give it a more dedicated try. I can imagine an organization that has institutionalized high levels of fluidity in its culture and operations. I can also imagine people who have internalized continuous transformation as a way of thinking and being.

The other thing that’s become clear to me is that although this model does not specifically outline the methods for helping people move from one level to the next, it appears to rest on an assumption of “center-out” or “top-down” change, where a core group of people defines the future state and systematically enrolls the rest of the organization in it. As you may have seen in my previous post on change roles, I’m convinced that this way of implementing change is often much less effective than approaches that include high levels of involvement and engagement from the very beginning, letting people prototype and test new ways of thinking and operating. This has the potential effect of letting people jump very quickly to the Internalization that comes from deep ownership, and then (because Internalization is fundamentally individual rather than systemic) working back through the process of creating the organizational norms, systems, structures, and processes that support the new ways of thinking and behaving. All of this can be encompassed by the commitment model if one recognizes that people can jump back and forth between levels rather than seeing it as a developmental model in which each stage must be preceded by the one before it.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on commitment. Leave a comment or drop me a line!

For the next installment in this series, click here.