Have you ever referred to an initiative as a burning platform? Do you hate the term and wish it would go away? Do you know the story behind it?

This is the sixth in a series of articles focused on classic elements of change management content, updated and augmented with my own perspectives and experience. In the first post, Strategic Risk Factors, I have provided some of the history behind this series. The series is primarily written for change management practitioners, but I hope it will also be useful for others who are interested in making organizational changes more successful.

Today’s Focus: Burning Platform

First introduced in Daryl Conner’s Managing at the Speed of Change, the metaphor of the burning platform has been used for nearly 30 years to describe a high level of urgency regarding a change initiative. While it is still in use today, it is unpopular with some in the change management world (I’ll discuss some of the reasons in my commentary). The material in the “Classic Model” section below is excerpted from Managing at the Speed of Change and used with permission of Conner Partners (formerly ODR).

*****************************************************

Burning Platform: Classic Model

The Story

At nine-thirty on a July evening in 1988, a disastrous explosion and fire occurred on an oil-drilling platform in the North Sea off the coast of Scotland. One hundred and sixty-six crew members and two rescuers lost their lives in the worst catastrophe in the twenty-five-year history of North Sea oil exploration. One of the sixty-three crew members who survived was a superintendent on the rig, Andy Mochan. His interview helped me find a way to describe the resolve that winners manifest.

From his hospital bed, he told of being awakened by the explosion and alarms. He said that he ran from his quarters to the platform edge and jumped fifteen stories from the platform to the water. Because of the water’s temperature, he knew that he could live a maximum of only twenty minutes if he were not rescued. Also, oil had surfaced and ignited. Yet Andy jumped 150 feet in the middle of the night into an ocean of burning oil and debris.

From his hospital bed, he told of being awakened by the explosion and alarms. He said that he ran from his quarters to the platform edge and jumped fifteen stories from the platform to the water. Because of the water’s temperature, he knew that he could live a maximum of only twenty minutes if he were not rescued. Also, oil had surfaced and ignited. Yet Andy jumped 150 feet in the middle of the night into an ocean of burning oil and debris.

When asked why he took that potentially fatal leap, he did not hesitate. He said, “It was either jump or fry.” He chose possible death over certain death. Consider this:

- He didn’t jump because he felt confident that he would survive.

- He didn’t jump because it seemed like a good idea.

- He didn’t jump because he thought it would be intellectually intriguing.

- He didn’t jump because it was a personal growth experience.

He jumped because he had no choice—the price of staying on the platform, of maintaining the status quo, was too high. This is the same type of situation in which many business, social, and political leaders find themselves every day. We sometimes have to make some changes, no matter how uncertain and frightening they are. We, like Andy Mochan, would face a price too high for not doing so.

An organizational burning platform exists when maintaining the status quo becomes prohibitively expensive. Major change is always costly, but when the present course of action is even more expensive, a burning-platform situation erupts. The key characteristic that distinguishes a situation made in a burning-platform situation from all other decisions is not the degree of reason or emotion involved, but the level of resolve. When an organization is on a burning platform, the decision to make a major change is not just a good idea—it is a business imperative.

Good Ideas and Business Imperatives

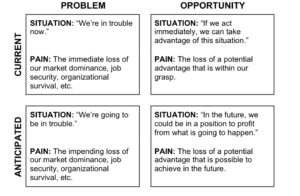

Two types of situations can generate the urgency to implement and sustain major change: The high price of unresolved problems or the high cost of missed opportunities. The price of unresolved problems can range from brief discomfort to a situation where recovery will be impossible. The price of missed opportunities can range from missing something interesting and enjoyable to missing a key element in moving from market leader to market dominance. The examples at the lower end of each continuum represent “good ideas.” As you move up the scale, the costs shift to those that are too expensive to pay. These situations that arise are burning platforms—business imperatives. The line between a good idea and a business imperative is subjective; each organization must define this distinction for itself.

Most organizations jeopardize their ability to sustain imperative changes because they embark on too many good ideas—changes that they want to do, are justified in doing, ones that will produce benefits and may be popular with the employees, but are not imperatives. To conserve assimilation resources, it is vital that organizations focus their attention on burning-platform-type situations.

How Pain Drives Change

The resolve to change that organizations develop during burning-platform circumstances can surface early or late in the game. When the resolve forms early, the company has anticipated what the price or pain of the status quo will be if the desired action is not taken. When the resolve develops late, the company is already paying a price for the status quo that is too expensive to bear.

Current pain is what inspires commitment to change late in a situation. Unfortunately, only short-term tactical a ction is possible at that point. When the resolve to change comes early, it is due to anticipated pain. Anticipated pain can be more powerful due to the extra time available in which to make strategic moves; however, it is often more difficult to convince people to take direct action when no current pain is felt.

ction is possible at that point. When the resolve to change comes early, it is due to anticipated pain. Anticipated pain can be more powerful due to the extra time available in which to make strategic moves; however, it is often more difficult to convince people to take direct action when no current pain is felt.

If a burning-platform situation is at hand, the issue is not will the necessary commitment to act be generated, but when. If your organization is facing a burning platform, don’t worry about generating commitment; worry about timing this commitment so that it can make a difference before irreversible damage is done.

In today’s irregular business environment, more and more organizations are finding themselves on burning platforms. Leaders are facing a status quo that they can no longer afford. Although transition may be disruptive and expensive, organizations feeling the heat understand that they have no choice but to change.

Change is not always necessitated by existing or anticipated problems; sometimes, emerging opportunities require major transitions. The urgency of burning platforms may result from either positive or negative circumstances, or it may stem from a visionary’s drive for excellence. Regardless, the common denominator for all burning-platform situations is urgency, necessity—resolve.

*****************************************************

Burning Platform: Linda’s Commentary

Metaphors and images are always so powerful! It’s hard to hear this story without mentally placing yourself on the edge of an oil rig, thinking about what you would do in Andy’s situation. It certainly creates a vivid picture of urgency. It’s also hard for me to hear this story without thinking of the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the people who made the choice to die by jumping rather than die in even more painful ways. Each of us has probably also had the experience of being drawn toward something we want—a relationship or a career, perhaps—and the high level of resolve it creates in us to take risks and pay whatever price is needed to obtain it.

Having said that, I’d like to separate the metaphor itself from the concepts it represents. Let’s take the concepts first. I really resonate with the idea that resolve can be driven by both problems and opportunities. I also agree that we can be motivated by both current and future discomfort, and that the timing is important—if we start too late, we don’t have much runway. If we start too early, it’s sometimes hard to get others to see the urgency.

The linkage between urgency, priorities, and change capacity is also very real. I have seen many organizations try to implement too many initiatives, failing to distinguish between good ideas and business imperatives, and choking on the cumulative resource and energy requirements. In these situations, they run the risk of failing at truly urgent changes.

I like the current/anticipated problem/opportunity grid as a way of creating real and impactful communication about the reasons for a change. Rather than trying to classify the change into one quadrant, it can be useful to cast the reasons for change into all four quadrants, as the things that create urgency for one person may be different from those that will convince another.

There are a couple of important cautions to keep in mind, of course. You can’t (and shouldn’t) turn every change into a burning platform. Burning platforms are identified, not created. If you are spinning up rhetoric to make it sound as though the world will end if your change does not succeed, you will not help the organization make wise choices about how to use its scarce resources. And if you are working on an initiative that is not a business imperative when compared to other issues the organization is facing, you need to be prepared for sponsors to become distracted and place a low priority on it compared to things that they see as truly urgent.

Now let’s tackle the metaphor itself. I personally have found myself using it less and less over time. Why? Well, first of all, I think it requires more explanation than I usually have time to give to ensure that people understand the true message. It very quickly becomes shorthand, and once that happens and people use it without understanding, it can very quickly be interpreted to mean that current/urgent problems are the only ones that motivate people to change. I think this is one of the core misunderstandings that has led to critiques of the term. Secondly, it can tend to drive binary thinking, both in terms of the decision about whether something is a burning platform and about the decision to take action. In real life, I find that priorities and urgencies shift a lot, and that most initiatives involve a series of leaps and mid-course adjustments. However, I will say that I haven’t yet found another metaphor with this much power to illustrate what deep resolve looks like.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. How do you help leaders understand what real urgency looks like? Are there stories and metaphors you use?